I’ve often heard from many flight instructors that they’ve learned more in the 30 hours of their flight instructor rating training than they have in their whole commercial pilot training – an exaggeration, I hope. When I ask the flight instructors to expand on that comment, I get a variety of answers ranging from increased skill in the airplane to deeper technical knowledge surrounding aerodynamics. Although I am happy to hear of the positive outcomes of their flight instructor training, I was often left wondering where the system failed them during their private and commercial training. The one common theme I noticed among all these casual encounters was a shift in the thinking patterns of these pilots. As they stepped into their new role as a Class 4 Flight Instructor, they were no longer able to just regurgitate what they learned as a private pilot. The flight instructors were expected to justify and persuade their students to fly an aircraft the way they wanted them to. In doing so, flight instructors constantly answered one important question, “why?”

Sometimes the answers to the students’ questions were not as simple as one may have hoped. Obviously, we need full power to conduct a take-off in a single piston aircraft. But when landing, a flight instructor may need to justify rudder before aileron, or aileron before rudder, in the transition from a crab to a sideslip. In this process of reasoning, flight instructors were forced to self-reflect on their own training to justify how they themselves flew an aircraft. This act of self-evaluation and analysis seemed to have opened a new way of thinking for many of the flight instructors. Through their flight instructor training, some instructors learned that a few of the flying techniques they were taught may have been inappropriate for certain scenarios or may have been taught incorrectly. Their self-reflection allowed them to shape the way they flew an aircraft and subsequently how they taught their future students.

Self-Reflection in Aviation

Self-reflection isn’t anything new in the field of education, with many studies pointing to numerous benefits for both teachers and students. The modern day reflective practice originated in 1910 with the work of John Dewey and has since been built on by scholars in a variety of disciplines. Michael Potter (2015) defines this practice as the activity of recollecting, reasoning about, and critiquing one’s experiences, beliefs, values, and practices for the purposes of evaluation and improvement. Engaging in a critical reflective practice extends beyond a simple examination of past knowledge and experiences. To me, being critical is a transformative process in which we change our behaviour because we have challenged and contextualized our past. Imagine two airline pilots, Gabby and Patricia, each with 10 years of experience. Gabby has 10 years of experience, while Patricia has one year of experience repeated 10 times. Gabby has learned from her mistakes and has grown into a better pilot, whereas Patricia has gone through the same motions year after year.

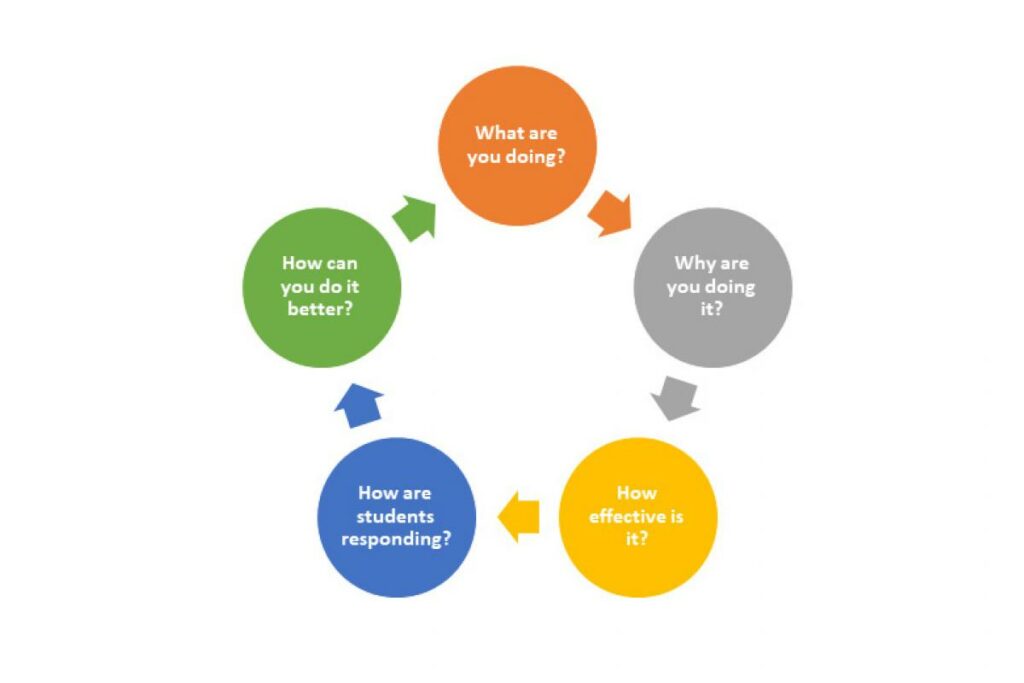

Engaging in critical self-reflection allows us to have more purpose with our actions, bridges a gap between knowledge and skill, identifies when a new approach may be required, allows us to break bad habits, and allows us to build trust with our students. Students have a chance to learn faster and better when engaged in critical self-reflection, and may be better prepared in future complex scenarios. One great benefit is that this type of practice can be taught by instructors, learned by students, and exercised by any pilot (including management at air operators). At this point, you may be wondering about how to engage in critical self-reflection.

How to be a Self-Reflective Flight Instructor

To begin, this practice requires a certain amount of vulnerability, honesty, and awareness of oneself. As an instructor, begin by asking yourself some of these questions:

- Do you know what purpose you have in your role?

- What type of flight instructor are you?

- Do you teach a student to pass a flight test or are you trying to prepare a student for what you think will help them once licensed or rated?

- What makes you uncomfortable as a flight instructor and what can you do about that?

- If your Chief Pilot or Chief Flight Instructor challenged one of your methods, how would you defend it?

Once you understand who you are and what you believe in as a flight instructor, it may be time to welcome feedback from your students and peers. You may choose to ask students what works for them and what doesn’t, or you can invite a fellow instructor to critique a pre-flight briefing.

As a flight instructor, you can facilitate this practice with your students in several different ways. But before this can be done, I must first note that the student must trust you. It is one thing for a student to be vulnerable with themselves, but another to do that with you. You must respect the student and ensure no harm comes to them while they engage in this practice. If a student has any fear or hesitation, they may easily abuse these activities rendering them unreliable or pointless. Trust is sacred in your relationship with your students, do not take advantage of it.

One of the most common activities I’ve seen students engage in is simply journaling. This can be done in the student’s own pilot training record or perhaps in a separate debriefing notebook. If using a learning journal, I suggest flight instructors provide examples to show what they feel is appropriate as a journal entry. You may also encourage students to engage in simple hangar talk around the airport or the simulator building. Hangar talk allows peers to engage with each other, learn from each other’s experiences, and adapt those experiences to their own lives. Lastly, my most important method is through constructive feedback to the student. As flight instructors, it is our jobs to facilitate student learning so they may make sound and appropriate decisions when they are not with us. Help students identify their strengths and areas to work on in a positive way.

I must conclude with a simple story from a colleague who recently completed a PPC. In

the de-brief, the examiner asked my colleague why he flew the aircraft in a particularly

“inappropriate” way during a localizer approach – still safe and worthy of a 3, nonetheless. His

answer, “that’s how I was taught by __.” The examiner explained that the background of

their instructor was a little outdated by modern standards and that the two pilots should have

questioned their instructors’ methods a bit more. An unfair, but common occurrence in

Canadian aviation at all levels of our industry. In this scenario, who could have engaged in a

self-reflective practice and who would have benefited from it? When you come up with an

answer, ponder about how you could be wrong. Try to learn more about yourself by thinking

about how you think.

References

Potter, M. K. with contributions from E. Kustra, N. Baker, L. Stolarchuk, and P. Boulos. (2014). Course Design for Constructive Alignment: Course Primer (Winter 2014 Edition). Windsor, ON.

Potter, M. (2014). Course design for constructive alignment: Course primer. Center for Teaching and Learning.