Ethics in Aviation

This article on Ethics in Aviation was written by Patrick A. Benton. Patrick A. Benton earned a Bachelor of Science in Aviation Technology and Management and a Master of Science in Manufacturing Administration, both at Western Michigan University, where he is now an Assistant Professor in the School of Aviation Sciences. The article was taken from the Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research (JAAER) and is available through the Ethics in Aviation link. The JAAER and this article are published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. You can learn more about is allowed under the license here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. This article is for non-commercial purposes and is designed to support pilots in commercial aviation.

Ethics and professionalism are an integral part of the aviation industry. High professional and ethical

standards are required of everyone in the chain from the designer to the pilot to ensure safe flight operations. This paper discusses ethical behavior and the ability to teach ethics and suggests methods that may be used by aviation faculty to enhance the ethical outlook of the aviation student.

INTRODUCTION

The safety of the aviation industry depends on the ethical and professional conduct of the people involved in the industry, yet the topic of ethics is strangely absent in the curricula of many university aviation programs. The already strained curricula do not lend themselves readily to additional course work in specific areas such as the study of ethics, although it is an honorable endeavor.

On the other hand, a topic as important to the aviation industry as ethics must not be left to chance. It is a topic that must be vocalized and acted out in all dealings with students so that the importance of ethical behavior is never left unsaid or in question. The questions then become: What is ethical behavior? Can this behavior be taught? How can ethics be integrated into the curriculum and be nurtured in our students?

WHAT ARE ETHICS?

It is impossible to define ethics in completely cognitive terms. Value judgments apparently are mixed in with skill-based judgments to result in complex behavioral decisions. It may be helpful, in attempting to analyze ethics, to draw a contrast between ethics and professional conduct. Professional conduct can be thought of as referring to cognitive matters that require skill and knowledge as the basis of decision making. Ethics, on the other hand, refers to values that are intrinsic in the person making the decision and that may or may not affect the outcome of the decision. These values include (but are not limited to) trust, a sense of right and wrong, concern for the welfare of others, responsibility for one’s actions, and adherence to one’s beliefs in the face of pressure to do otherwise.

To illustrate this point, consider a situation in which a maintenance technician is told the boss has an important trip to make and the aircraft must be ready to fly first thing in the morning.

The aircraft requires some maintenance before the next flight but a needed part will not be available in time for the flight. Does the maintenance technician defer the required repair, try to get by with an incorrect part, or tell the boss the flight will have to be canceled? From a standpoint of professional conduct, the technician knows the incorrect part is not appropriate and the maintenance must be performed. Flight canceled, case closed, right? Not so fast. Let us add some other information. The last flight had to be canceled due to mechanical problems, the company is down-sizing, and the flight department may be in jeopardy, so the technician is concerned about a future with the company. This new information brings in a set of decision-making variables that are not cognitive based and cannot be resolved as easily as cognitive problems.

This example, although simplistic, illustrates the multifaceted, complex nature of decisions. Decisions often must be made in the context of a situation with thought given to interpersonal as well as systemic impact. And because of this complexity much room exists for ethics-based influence in most decisions.

Unfortunately, professional conduct and ethical conduct are not dichotomous. That is, they are not mutually exclusive.

Ethics and professional conduct can be thought of in whole as professionalism that involves more than simply expertise, but involves a commitment to a set of values and moral principles that are accepted by society (Kipnis, 1992).

CAN ETHICS BE TAUGHT?

Historically, the teaching of ethics has been controversial In the past, psychologists and philosophers commonly believed that the formation of ethical beliefs was a part of the formation of a person’s character and thus was established by the age of 10 or 12. This belief was rooted in and strongly influenced by Freud’s theory that the superego is the basis of morality and is therefore established early in life.

Modem psychological research, however, does not support this idea. It is now thought that a person’s moral beliefs continue to mature as the person becomes more educated and aware of the multiple perspectives typically associated with decision making in the adult, professional world (Piper, Gentile, & Parks, 1993). This being the case, it would seem that there is an opportunity, perhaps even an obligation, to include ethics education in university aviation curricula.

HOW CAN ETHICS BE INTEGRATED INTO THE CURRICULUM?

If we accept that it is not too late to teach ethical behavior and that the subject should be taught in aviation programs, we then must deal with the question of how to go about it. The easy answer is to force an ethics course into the curriculum, but the impact of formal courses on ethics is limited. Typically, these courses are case-based and succeed only in defining terms and showing examples, through case studies, of the consequences of unethical behavior. These courses usually are perceived by students as boring and removed from reality. Worse yet, the courses do not put the ethical, dilemmatic decision-making process into context for students (Piper, Gentile, & Parks, 1993). And although most successful university aviation students are talented and highly motivated people, most of them have not experienced the diversity and complexity of decision making in the professional world. They have not learned to critically reflect on issues that influence society and themselves. They have a limited view of what is at stake when tough decisions have to be made.

The challenge for aviation faculty may be to encourage reflective thinking and to try to make students aware of the total impact of the decisions they make. The most effective way of doing this may be to address the topic of ethical behavior in every course and activity as opportunities present themselves; that is, teaching ethics across the curriculum. The faculty must engage in a concerted effort to introduce ethics discussions into the curriculum. However, these discussions must not be so intense and rigorous as to supplant the functional topic and, in fact, the effort may be so subtle as to be almost invisible to the student. This approach must be supported by and have the participation of all the faculty because if only one of the faculty is addressing the topic of ethics the students may think the professor has ulterior motives.

Integrating ethics discussions, however, is challenging for faculty for many reasons. Mary C. Gentile, in a study at the Harvard School of Business in 1993, uncovered some of the reasons why faculty see ethics discussions as such a challenge.

For example, faculty may not like the unpredictable nature of ethics discussions, which can pop up at any time. It is difficult to plan an ethics discussion and still have the same impact as an impromptu discussion. Many faculty may feel they are not adequately qualified to discuss the topic because of their technical background and education. Ethics may seem like a philosophical subject that faculty are not comfortable with or knowledgeable about. Faculty may feel that students will not take ethics discussions seriously or that they may view the discussion as insipid commentary that takes up time in an otherwise technical or functional class. Faculty also may feel that it may be a waste of time to even try to discuss the subject because they cannot evaluate the student’s critical thinking on ethics.

By discussing these concerns among ourselves, we may be able to overcome some of the barriers that have kept us from integrating ethics into the functional courses of our curricula. Such dialogue would be a good first step in establishing an ethics across the curriculum program. It also may be useful to discuss the reasons for promoting ethical behavior and the benefits we stand to gain. A periodic review of the ethics program also would be appropriate and helpful. Sharing details of how issues came up, how the students responded, and the impact on the class, as well as other pertinent observations would lead to evaluating our techniques and the effectiveness of the ethics program.

THE ETHICAL ROLE MODEL

The aviation educator has another important role in the development of ethical and professional behavior in future aviation professionals.Beyond incorporating ethics across the curriculum, the aviation faculty must adopt the highest ethical standards for themselves and be an ethical role model for their students. The time-honored concept of teaching through example may well be the most effective method. This observation may seem so basic as to be almost trite: Surely the university professor has the highest ethical standards, right? Maybe not. Certain conduct and habits may be perceived by the student as unethical and may set the wrong example without the professor even realizing it. And if this is the case, we are teaching through our example that it is acceptable practice to act with less than the highest ethical standards.

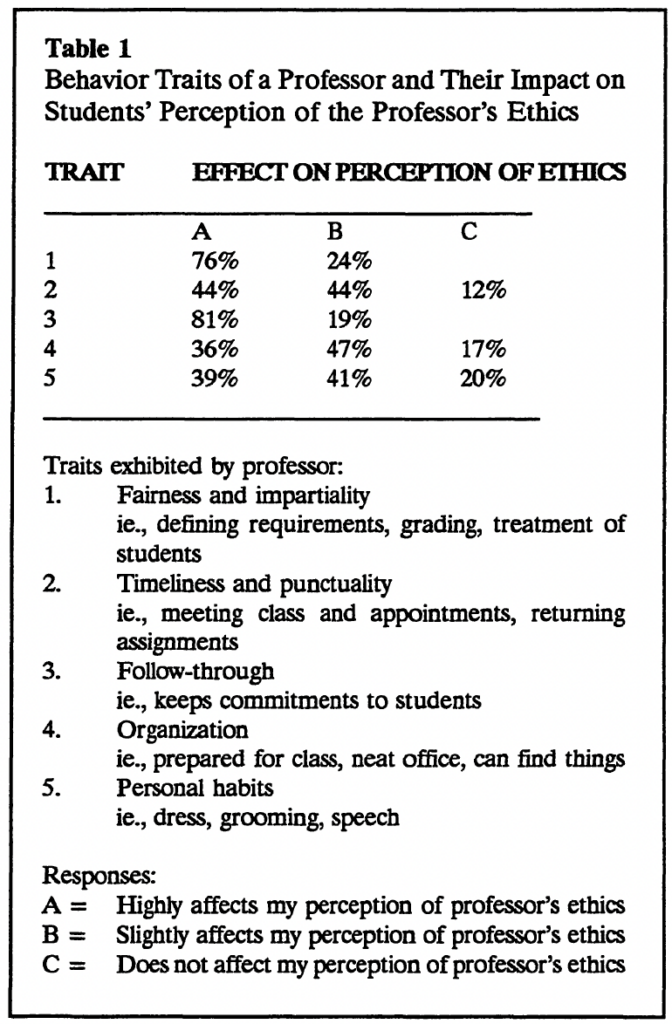

To determine whether a professor’s conduct has any impact on students’ perception of the ethical standards of the professor, a survey was conducted of 59 junior- and senior-level aviation students at Western Michigan University. The students were given five behavior or personal traits and asked whether those types of behavior had a great impact, a slight impact, or no impact on their perception of the professor’s ethics. Table 1 shows the results of this survey.

The results show that the behavior traits of a professor are viewed by the students as a indicator of the ethics of the professor. It follows that these behaviors set ethical examples for the students even though the professor may not realize it. Fairness and impartiality and follow-through scored the highest. One hundred percent of the students said these traits were indicators of the professor’s ethics, with an overwhelming majority indicating these traits highly affected their perception. It appears that these traits are the most visible facet of a faculty member’s ethical demeanor and thus provide the best opportunity to set a good ethical example.

Fairness and impartiality may be promoted by publishing in the course syllabus and discussing the rules of the course on the work expected, grading policy, attendance, and so on. The rules then must be adhered to and applied equally to all students. This policy helps send the message that there are strict rules in the aviation world and no room for compromise of the rules. Follow-through is another behavior that strongly influenced the students’ ethical perception. Follow-through, or keeping commitments, is a cornerstone of high ethical standards. It is not surprising that students viewed this trait as a strong indicator of ethics. The faculty must respect the students and keep commitments to them. We must never adopt the attitude that they are only students and so it is not necessary to make or keep commitments. If a laissez faire attitude is displayed toward students, they may adopt that behavior and take it with them into their career, which is an undesirable educational outcome.

Other personal traits students were asked to judge were timeliness and punctuality, organization, and personal habits such as dress, speech, and grooming. Although these traits may not come to mind immediately when discussing ethics, surprisingly enough they do seem to influence students’ perception of ethical standards. Timeliness and punctuality were viewed by 88% of the students as having some connection to ethics. Half were strongly impressed, while the other half were slightly impressed. But the fact is that punctuality is perceived as an ethical trait

Equally surprising are the areas of organization and personal habits. An overwhelming majority (83% and 80% respectively) felt that these traits have something to do with ethics. Organization has a strong tie to ethics for 36% and a slight tie for 47%, while personal habits have a strong tie for 39% and a slight tie for 41%.

Finally, the survey asked the students for any comments on ethics or teaching ethics. About 25% of the students commented in writing that they felt spending large amounts of time “preaching” about ethics is a waste of time and that they are easily bored with this type of discussion. At least half the students made the same comments verbally after turning in the survey. This finding seems to indicate that if we are going to inject ethics discussion throughout the curriculum, we must keep the discussion brief and subtle. The survey also appears to show that almost anything done to interact with students is likely to affect their view of ethical standards. And if example really is the best teacher, then we are constantly sending out ethics messages through our behavior. It is apparent that we must accept our post as role model and exemplify the ethical standards we wish to instill in our students.

CONCLUSION

Contemporary research has shown that a person’s ethical standards can be changed through education. In other words, ethics can be taught. Research also has shown, however, that courses in ethics and preaching about ethics is largely ineffective and is not well received by students. The greatest effect on the ethical standards of a student can be achieved through a two-prong approach. First, a person must be able to critically reflect on the impact of decisions that he or she makes. This process requires a thorough understanding of the system in which they are a decision maker and the ability to critically reflect on a decision. Understanding the system is part of the core of the aviation subject and is easy for us to teach. But critical reflection about decisions is the part that we are not skilled at, or at least not skilled at getting our students to do. This is the part that we must improve and inject into our courses. Care must be taken not to make the reflection exercise too overt as to bore the students and tum them off to the subject entirely. Secondly, we must teach ethics through example. And it is important to keep in mind that almost everything we do sends an ethical message to the student. We must ensure that this message is one of high ethical standards.

REFERENCES

Kipnis, K (1992). Engineers who kill: Professional ethics and the paramountcy of public safety. In J. H. Fielder & D. Birsch (Eds.), TheDC-10 case: A study in applied ethics, technology, and society(pp. 143-160). Albany, NY: State University of New York.

Piper, T. R., Gentile, M. C., & Parks, S. D. (1993). Can ethics be taught?: Perspectives, challenges, and approaches at the Harvard Business School. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

Scholarly Commons Citation

Benton, P. A. (1995). Ethics in Aviation Education. Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.15394/jaaer.1995.1147

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Aviation/Aerospace Education & Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact commons@erau.edu.